Can Bias Prevent Women Running For Office From Having A Fair Shot?

Our guest authors today are Anthony Carnevale and Nicole Smith. Dr. Carnevale is Director and Research Professor and Nicole Smith is Chief Economist and Research Professor at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. This piece was originally published here on CEW's Medium page.

When the presidential candidates introduced themselves on the Democratic primary debate stage in 2019, they weren’t the usual crowd of contenders. Among more than 20 candidates, six women representing a range of geographic areas and policy positions took the podium. One hailed from California, and another from Minnesota. Some voiced support for Medicare for All, while others opposed it.

Women have made significant advances in their representation in US politics within the past 50 years. Though Hillary Clinton lost her bid for the presidency in 2016, she won the popular vote and made history as the first woman to be nominated for the presidency by a major party. In 2018, a record number of women ran for Congress — and many won their elections. Although the field of women running for the Democratic presidential nomination has narrowed from six to four, Senator Elizabeth Warren remains a frontrunner in several polls.

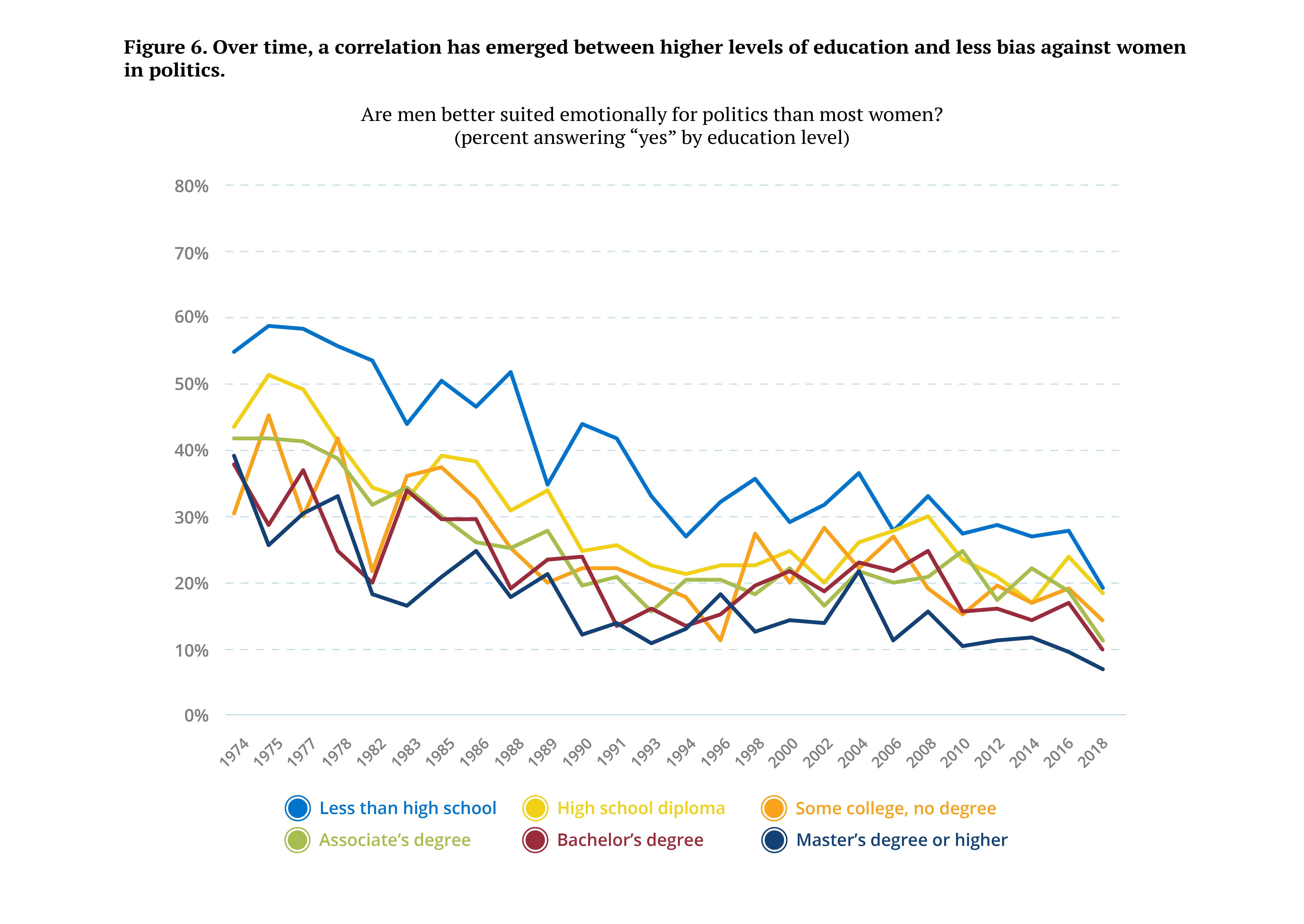

Despite this progress, bias still remains against women in politics. According to our analysis of recent data from the General Social Survey, while this number has fallen over the past 50 years, 13 percent of Americans still believed in 2018 that most women are not as emotionally suited for politics as men. This bias may have the potential to decrease women’s chances of being elected to political office.

Our research shows how bias against women has shifted among different demographic groups in the past 50 years. In the 1970s, women over the age of 35 were most inclined to say that women are less emotionally suited for politics than men. By 2018, however, the percentage of older women expressing this bias had declined, reaching a similar level as that of young women. A gap remains between strong Republicans and strong Democrats; as of 2018, strong Republicans were almost three times as likely as strong Democrats to show bias against women in politics.

Today, there are no major differences by age, race, sex, or income among respondents who believe men are better suited for politics. But those with higher levels of education stand out for showing less bias against women in office. By 2018, only 7 percent of respondents who had a master’s degree or higher said that men are generally better suited emotionally for politics than most women, compared to 19 percent with less than a high school diploma. Education may serve as an antidote to this bias, though its impact many not be as direct as our data suggests. Results of the 2016 general elections showed a decided shift toward more conservative patterns across educational backgrounds.

Two of the four women remaining in the presidential race are set to take the stage again at the December debate. And many more women are poised to run in local and congressional elections, even though remaining bias threatens to affect their chances of election. Still, if the Democratic debate stage is any indication, women’s representation in politics will continue to grow.