When "Prisoners of Time," a study of the use and misuse of time in U.S. schools, came out a few months ago, people latched on to the apparent relationship between student achievement and the length of the school day and school year.

The report, which was produced by the National Education Commission on Time and Learning, confirmed what some already knew--that the 180-day school year, which is the U.S. average, is shorter than that of most other industrialized democracies with good school systems. But the study also gave us some shocking figures about the hours spent learning core subjects. Our students spend less than half of their actual school time--only 41 percent--learning core subjects like English, science, history or math. So by the time they graduate from high school, they have, on average, studied core subjects for 1,460 hours, while Japanese students have spent 3,170 hours and German students 3,528.

The conclusion seemed obvious to many people: If practice makes perfect, no wonder American students often score more poorly on international examinations than students from other industrialized countries. The solution seemed obvious, too: a longer school day or school year or both. Of course, those who call for this don't usually talk about the price tag. How likely is New York City or Los Angeles or Dade County to come up with the millions of dollars it would cost to add another hour to the day or 30 or 45 days to the school year when education budgets are already being cut to the bone?

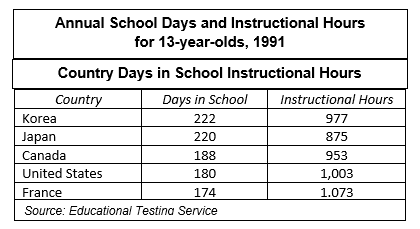

But even if we had money to throw at the problem, would adding more time get our students to achieve at the same high levels as kids in other industrialized democracies? I doubt it. For one thing, the correlation between time spent in class and achievement is not as simple and straightforward as it seems. "Prisoners of Time" points this out, and it is plain from the following table, which appeared in "Understanding the Performance of U.S. Students on International Assessments" (National Center for Educational Statistics, Education Policy Issues: Statistical Perspectives, April 21, 1994):

The information here pertains to 13-year-olds rather than high school students, but differences in achievement similar to those we see in high school already exist among 13-year-olds. And more time in class does not seem to match up with higher achievement. French students, who master a far more challenging curriculum than our students, do spend more hours in class than American kids. But Korean and Japanese students, who consistently outperform our kids, spend considerably fewer hours in class.

The issue, then, is not merely how much time kids spend in class; it's what they are doing while they're there. The successful education systems of other industrialized democracies have rigorous national or state standards for what their students should learn in school, and they base their curriculums and assessments on these standards. In this country, curriculums vary from district to district and even school to school--or classroom to classroom. That's because, while states establish core course requirements, they don't define what should be in these courses--like what a student who passes American history is supposed to know and be able to do. And we're big on loading up core courses with add-on topics that arise out of the latest fad or social problem.

The standards-driven systems in other countries are also able to make better use of available time. Because students are working to meet well-understood standards, teachers know what their students need to learn--and what they have already learned. In the U.S., a teacher can never be sure what students in a class learned the year before. As a result, our teachers have to waste about 30 percent of class time reviewing material from the previous year before moving ahead with the current year's work.

The Goals 2000 legislation that President Clinton recently signed into law proposes that states establish standards and curriculums and assessments based on those standards. This gives us the opportunity to create the rigorous and focused curriculums that help make students in other countries successful. However, the entire effort could come to nothing if states simply allow each district and school to do its own thing. And of course kids in other countries work hard to meet the standards because they know something they want--a job or entry into college or an apprenticeship program--depends on it. Stakes like these will also have to be part of our new system if we want it to work.