A recent New York Times story found that employers don't believe schools are preparing young people for their workplaces. But this may be the result of a phenomenon known as the "self-fulfilling prophecy." Self- fulfilling prophecy is a sociological term used to describe events that occur because people believe they will. The classic example is large numbers of people making a run on a bank because they believe it is failing. Their run makes the bank fail.

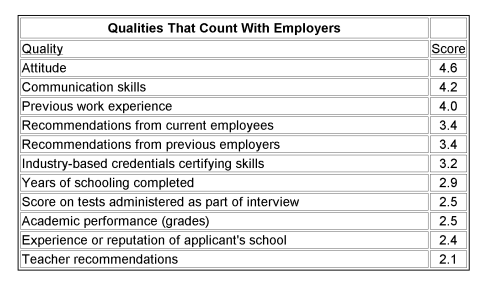

The Times story ("Employers Wary of School System: Survey Finds Broad Distrust of Younger Job Applicants," February 20, 1995) was based on a national survey done by the Census Bureau for the U. S. Department of Education. The Census Bureau surveyed 3,000 employers across the nation last August and September. They were asked, "When you consider hiring a new nonsupervisory or production worker, how important are the following in your decision to hire?" The Census Bureau used a scale of 1 through 5. A score of 1 indicates that the quality is not important or not even considered while a score of 5 indicates that the quality is extremely important.

Clearly, most employers give little weight to the last three items, which deal with the performance of students in school. In fact, they are more interested in how many years students spent in school than in what they did while they were there. (See the fifth item from the bottom.) This probably means that employers seldom bother to ask for teacher recommendations or transcripts of grades, and they probably don't pay any attention to where a student went to school. Is there any doubt that the word gets back to students who are still in school that these things don't count? And if they don't count, why should students work hard to get good grades or attend schools with reputations for high standards rather than easy ones?

It's obvious that the less attention employers pay to school performance, the less incentive kids have to achieve and the more poorly prepared they will be. One way out of this problem would be for employers to ask for information about student achievement and take it seriously. But it's not that simple.

In Japan and Germany, where there are close links between what students do in school and the jobs they get when they graduate, employers know what a grade means. Like most other industrialized democracies, these countries have school systems with external standards and examinations. If students take certain courses and pass certain exams, there is no question about the material they have studied and their level of achievement. This is true for students going on to university, but it is also true for young people who are entering the job market right from school.

In the U.S., every school district is free to set its own curriculum and standards, and employers have no way of figuring out what an A in algebra means -- or even whether "algebra" is just consumer math with a fancy name.

Until businesses can have confidence in student transcripts and recommendations, they will go on disregarding them -- and students will continue to conclude that what they do in school does not count. States that are now working on Goals 2000 should keep this in mind. The external standards they create for their students can help re-establish the essential link between school achievement and the job market.